AMM Critical Review: Qiheng Liu, Recoding Reality

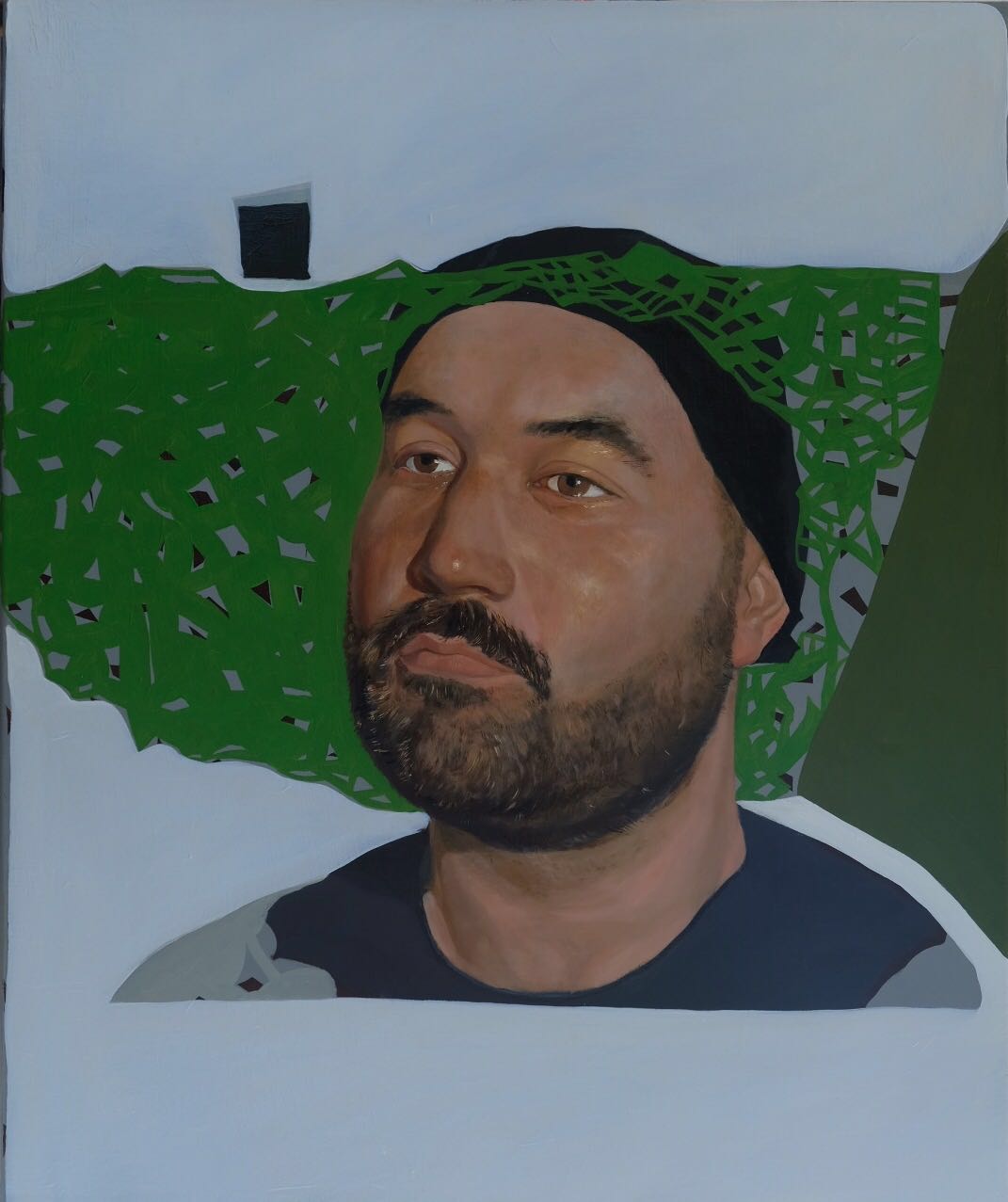

Purity and precision are evident in the paintings of the artist Qiheng Liu. He is a visionary and a superb technician. The clarity of his style in his latest series of paintings displays the influence of the portraiture of Hans Holbein the Younger. Liu doesn’t paint portraits, though. He takes pleasure in dismantling the idea of a portrait and reconstructing it, using his own code of images to invite the viewer into a secret sphere where playfulness and power balance each other as art comes into being.

The paintings we might at first perceive as portraits are for the most part labeled “Untitled.” When there is a title, it is reference to the placement of dissonant elements in the composition, such as “White Cube” or “Black Square.” These dissonances work in the same way a jazz musician riffs far from the melody before returning to a recognizable tune.

The faces, though, are unmistakably drawn from reality; from the artist’s circle of friends, in fact. By leaving the works untitled, rather than using the names of real people, or by referring to shapes (square, cube) that must be forced into reality since they do not exist in the natural world, he eschews the commercial nature of portraiture.

This is a resounding theme that surprises again and again. He can depict faces without debt to names or language. In this way, a face is another way of focusing, a study that allows the artist to expand his vision until there is no hierarchy of imagery. The face of a man or woman is no greater or lesser than one of his paintings of a crumpled sheet of paper.

The painter quite obviously takes pleasure in capturing certain exact elements from what is known as reality and then exploring the freedom that comes of placing them in a composition that challenges the known or the familiar. This is the approach of a truly original mind.

What is startling is that these are the efforts of a young artist. Only this year did Liu receive his first solo exhibit anywhere, in a Tribeca gallery, auspiciously enough. It certainly seems that a more mature artistic talent is being brought to bear. Then again, it is often that way with the good ones, who are fewer and farther between than one might imagine in a society that accepts the notion that excellence is decided by yelping and twittering on social media. Pure visual art never has been for the masses. Excellence reveals itself as extraordinary, always.

If Liu’s use of destabilization and juxtaposition are jazzy in his examination of what it is to not make a portrait, the play of these energies in some of his earlier works is positively symphonic. Each painting is a conversation within itself, between the depicted and the implied, and the language can be secretive. Most include glass bottles.

These glass bottle paintings seem to this viewer to be evidence of a devious humor doing serious work. At first glance, they appear to be related to still life composition, and maybe they are, but in a way that deconstructs the very idea of a still life. Here the artist gives the viewer more verbal clues as to what is going on. He has titles for most of this series of canvases.

In About to Explode, a cherry bomb type firecracker is inside and on the bottom of a glass pickle jar. Or is it a cherry bomb? What first appears to be a fuse continues upwards, its length piercing the jar top and extending until it connects with a red cube that floats in the air, beside a floating bronze colored orthotope – rectangular cuboid – that floats above a white cube. All this plays out in front of another, almost neutral colored cuboid that stands monolithically on the same plane as the jar.

The jar itself is a study of how light reflects off glass while passing through it – a dichotomy that is central to the nature of clear glass jars and bottles. Throughout this series, every glass bottle and jar in each painting is unique within the series. No two containers are alike.

In Falling Down, things appear to be rising, lifting themselves up, exerting energy to defeat gravity. The glass bottle here seems stabilized in mid-air, suspended in place and space by a red string through the bottle top. It contains a cider-vinegar-colored liquid. This is all in front of a white square of canvas on which two cuboid orthotopes are painted – a painting within a painting in which nothing is natural while the nature of reality is toyed with. The white sheet of canvas itself is pulling away from the surface to which it is affixed, at the bottom. In other words, it too is lifting up, not falling, as the title implies. Spread beneath all this is a patchwork quilt, rising from the “floor” – sort of a magic carpet, if you will.

Falling Down also examines another interesting contradiction that exists in the relationship between glass and light. The bottle casts a shadow. Think about this for a moment. Light that passes through clear glass also casts a shadow of the clear glass object. The painter is steering the viewer’s attention, creating a conversation about a natural contradiction which we see all the time but most likely do not notice.

In What You See Is What Is Going To Be, Nice to Meet You, Here I Am, and all the other titled and untitled works in the glass bottle paintings, the artist maintains this aesthetic playfulness – without sacrificing the power of his technique and vision. None of this is gimmicky at all. There is a thoroughness to the artist’s approach that displays the relentless quality that comes of passion. So, now arises the question, what is Qiheng Liu up to?

He may be an emerging artist, but he is emerging fully formed. These paintings are clear evidence of an artist who understands the absolute necessity of controlled self-expression, which is at the basis of any true artist’s oeuvre. One also cannot help but look forward and ask, “What’s next?”

Stephen DiLauro is a recognized authority on art and artists. His essays, articles and criticism have appeared in many prominent publications, including Smithsonian, Miami Herald Sunday Magazine, American Artist, Philadelphia Inquirer, as well as in books, catalogs and monographs. © 2019 First International Serial Rights. All other rights reserved.