Jon Isherwood on Broadway

Broadway Blooms: Jon Isherwood on Broadway is a sculpture exhibition presented by the Broadway Mall Association along the Broadway malls between 64th and 157th Streets (from Summer 2021 to Spring 2022).

The Broadway Mall Association (BMA) is a nonprofit that stewards, advocates, and cares for the five-mile-long environmental resource in the heart of Upper Manhattan. Eighty- three verdant malls stretch from 70th Street to 168th Street from the Upper West Side through Harlem to Washington Heights. BMA’s Art on the Malls program brings contemporary art exhibitions to the diverse communities along the Broadway malls for the benefit and engagement of residents and visitors. Broadway Blooms: Jon Isherwood on Broadway is the 13th public art project in the BMA’s exhibition series launched in 2005.

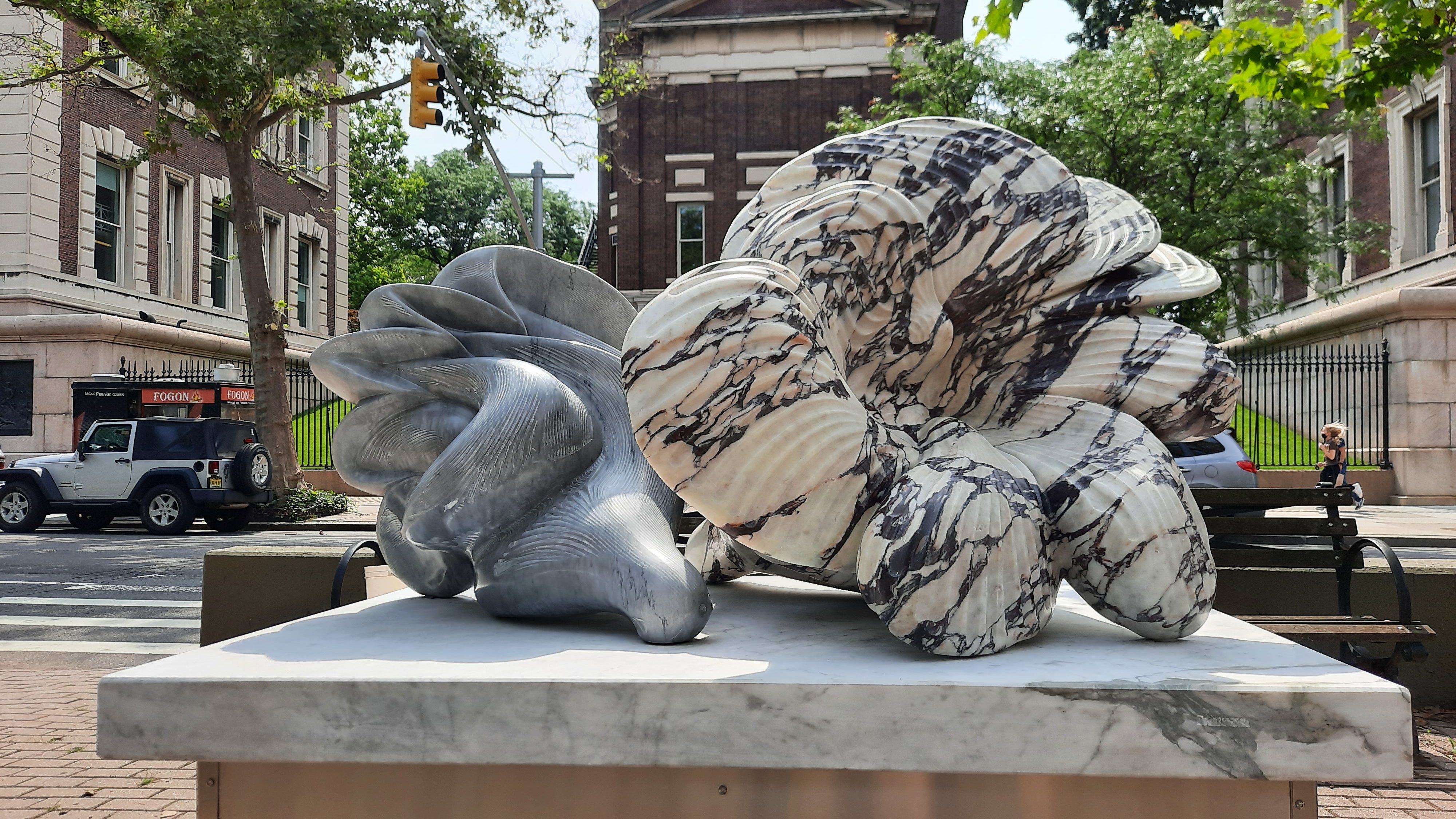

Fantastico Arni marble

56 x 96 x 52 inches

Broadway & 72nd Street

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

Jon Isherwood (b. 1960, UK) lives and works in Hudson, New York. He studied at Leeds College of Art and Canterbury College of Art, UK, and at Syracuse University, New York. Isherwood’s work has been widely exhibited in public museums and private galleries in the US, Canada, Europe and China. He is the recipient of a Jerome Foundation Fellowship, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation award and an Honorary Doctorate from the University of New York at Plattsburgh. He has lectured at numerous colleges and universities in the US, Europe and China. He is the President of the Digital Stone Project.

Isherwood is presently working on a commission for the new US consulate in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and a new sculpture will be featured at the Italian stone theatre exhibition, Verona, Italy in September 2021.

The following is an excerpted, edited conversation between Jon Isherwood and Lilly Wei.

Bardiglio Imperiale marble

47 x 51 x 51 inches

Broadway & 79th Street

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

Lilly Wei: How did you become involved in this project?

Jon Isherwood: Anne Strauss, the curator from the Broadway Mall Association’s Public Art Committee, invited me to do an exhibition about four or five years ago and I was, of course, happy to do it—although it became more challenging—and exciting—when I realized it would be eight locations, not one, as I had first thought. After all, very few spaces can extend an exhibition and the experience of an artist’s work over more than four miles.

L: Verde Rameggiato marble, 33 x 55 x 43 inches

R: Rosso Cardinale marble, 39 x 70 x 31 inches

Broadway & 96th Street

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

LW: How did you begin to map out your project, to decide what you would show?

JI: I started out by thinking about how art functions in public spaces and how it interacts with all the different kinds of viewers who will see it. I was very conscious of how it might be read even then, which was years before the pandemic, and before all the controversy during these past long months about monuments in public spaces. Because I wasn’t familiar with Broadway, I walked it from 64th Street to 157th Street. I knew that neighborhoods would change, and that each mall along the route would have its own identity in terms of the plantings and be surrounded by a distinctive community—I just didn’t know how distinctive. It was truly a journey through several different cultures.

Calacatta Gold marble

57 x 66 x 66 inches

Broadway & 103rd Street

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

LW: You said the idea to install flower sculptures came to you immediately.

JI: Yes, I was struck by the plantings in the medians, blooming with flowers. I thought my contribution should be about beauty, pure nature, not usually seen in an urban setting like Broadway. I had just completed some work for the Peninsula Hotel in China and was already thinking about immersive floral surfaces, like those in Monet’s Giverny paintings and his murals at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, Georgia O’Keeffe’s calla lilies, and Manet’s peonies. Looking at them was like staring into a bouquet. I then thought of flowers in bouquets as gifts to the viewers, something that would give joy.

L: Breccia Viola marble, 41 x 39 x 35 inches

R: Bardiglio Imperiale marble, 33 x 31 x 28 inches

Broadway & 117th Street

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

LW: Tell me a little about the placement of the work. For instance, the one at Lincoln Center, the starting point.

JI: The lead work is The Earth Laughs. I was investigating how to do this, how to present a flower. Because it was in Dante Park at Lincoln Center, I thought about opera, dance, music, the stage. That led to thinking about how flowers, bouquets of flowers, were thrown on the stage after a performance and I thought about how the bouquet lies on the stage. It was a beautiful moment. I had an image of that in mind. My resolution was to enlarge the flower, open it up to resemble the shape of a bouquet. And I was using stone. I wanted the veining in the marble to radiate from the center to indicate the illusion of fluidity, movement, growth, and shading. I wanted to create a sense of flow in the static, solid stone, as well as volume, dimensionality.

Bardiglio Imperiale marble

72 x 40 x 16 inches

Broadway & 148th Street

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

LW: And some of the others?

JI: Some of the smaller sites I thought of as places to meet, so some of the flowers can approximate benches, like A Gift between Two at 72nd Street. After Giverny, at 148th Street, is upright, the surface foliated, as if looking through branches and leaves to the sky, through solid and transparency, light and dark. At 157th Street, I wanted it to be particularly forceful, as the culminating piece. Called The Gifting Angel, the form swells, like wings outspread, triumphantly.

Bardiglio Imperiale marble

65 x 58 x 18 inches

Broadway & 157th Street (Ilka Tanya Payán Park)

CREDIT: Jon Isherwood

LW: The colors of the marble are gorgeous as are their names: Rosa Portogallo, Verde Rameggiato, Calacatta Gold, for instance. Where does the stone come from?

JI: Pietrasanta, Carrara, mostly, but The Earth Laughs’ rose marble is from Portugal. I choose carefully, for color and pattern. The veining contours it, giving it a sense of the body and its physicality. My work is a dialogue with form and surface.

LW: Like so many other projects, the pandemic delayed the opening of “Broadway Blooms.” How did that affect your project?

JI: It became a more celebratory moment when the show finally opened after a year’s delay and so much loss—although I know it’s not over yet. It took two weeks to install the works and I have never felt such enthusiasm. Everyone was so happy, so grateful. And I like that community members are recruited to maintain the sites, to clean them up, have a stake in them. I became more aware of all the communities along the route and placing work at the different locations was a way for me to connect, but it was also a way to join those locations. At every mall, there is a plaque that identifies all the sculptures in the project, linking them together, another way to connect. It was enlightening. I learned something about public art and its audiences and how integral they are to each other.

Lilly Wei is a New York-based art critic, art writer, journalist and independent curator whose primary area of interest is global contemporary art.